The Gender Biases That Shape Our Brains

The toys we give to children and the traits they are assigned can have lasting impacts on their lives, writes Melissa Hogenboom.M

My daughter is obsessed with all things girly and pink. She gravitated to pink flowery dresses that are typically marketed for girls before she even turned two. When she was three and we saw a group of children playing football, I suggested she could join in when she was a bit older. “Football is not for girls,” she replied, firmly. We carefully pointed out that girls, though in the minority, were playing too. She was unconvinced. However, she’s also boisterous and loves to climb and jump, attributes often described as boyish.

Her overt ideas about what girls and boys should do were somewhat unexpected so early on, but considering how gendered many children’s worlds are from the outset, it’s easy to see how this occurs.

These initial divisions may seem innocent, but over time our gendered worlds have lasting effects on how children grow up to understand themselves and the choices they make – as well as how to behave in the society they inhabit. Later, gendered ideas continue to influence and perpetuate a society which unknowingly promotes values linked to toxic masculinity, which is bad news for all of us, however we identify. So how exactly does our obsession with gender have such a lasting impact on our world?

Story continues below

Even though many girls play football – and the recent success of women’s professional soccer – it is still seen as a largely male sport (Credit: Javier Hirschfeld/Getty Images)

The idea that women were intellectually inferior to men was regarded as fact several centuries ago. Science has long sought to find the differences that underlined this assumption. Slowly, numerous studies have now debunked many of these proposed differences, and yet our world remains stubbornly gendered.

When you think about it, this is wholly unsurprising due to the way we are socialised as infants. Parents and caregivers don’t mean to treat boys and girls differently, but evidence shows they clearly do. It starts before birth, with mothers describing their baby’s movements differently if they know they are having a boy. Male babies were more likely to be described as “vigorous” and “strong”, but there was no such difference when mothers did not know the sex.

Ever since it was possible to identify biological sex from a scan, one of the first questions asked of prospective parents is whether they are having a boy or a girl. Before then, the shape and size of a bump has been used to guess the sex, despite there being no evidence this works. More subtle are the different words we use to describe boys and girls, even for the exact same behaviour. Throw gendered toys into the mix and this reinforces the subtle traits and hobbies that are already assigned to male and female.

You might also like:

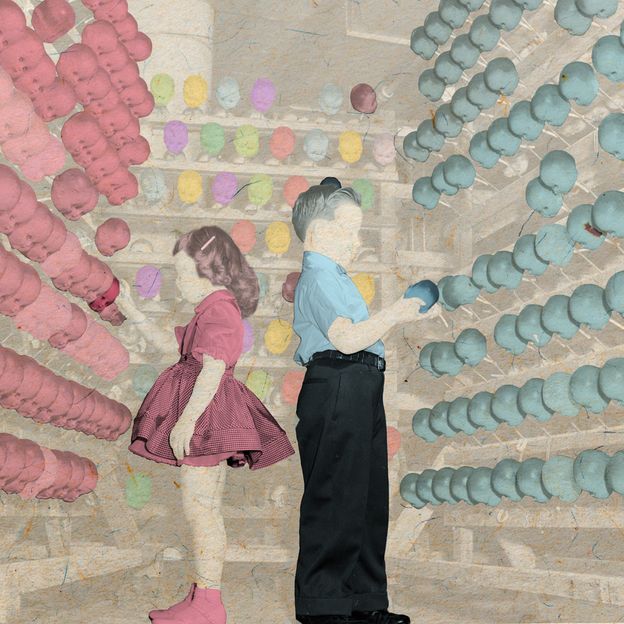

The way children play is a hugely important part of development. It’s how children first develop skills and interests. Blocks encourage building whereas dolls can encourage perspective taking and caregiving. A range of play experiences is clearly important. “When you only funnel one type of skill building toys to half of the population, it means that half of the population are going to be the ones developing a certain set of skills or developing a certain set of interests,” says Christia Brown, a professor of psychology at the University of Kentucky.

Children are also like little detectives, working out what category they belong to by constantly learning from those around them.

As soon as they understand what gender they fit into, they will naturally gravitate towards the categories that have been thrust upon them from birth. That’s why from the age of about two, girls tend to navigate more to pink things while boys will avoid them. I witnessed this first-hand when my then two-year old stubbornly refused to wear anything she perceived as slightly boyish, despite my futile attempts not to overtly gender her clothing early on.

Although boys are not typically given dolls to play with, they can enjoy caring for them as much as girls (Credit: Javier Hirschfeld/Getty Images)

It’s no surprise then that pre-school children learn to identify with their gender so young, especially as parents and friends tend to give children toys associated with their gender early on. Once children understand which “gender tribe” they belong to, they become more responsive to gender labels, explains Cordelia Fine, a psychologist at the University of Melbourne. This then influences their behaviour. For instance, even how a toy is presented can change a child’s interest in it. Girls have been found to be more interested in typically boyish toys if they were pink, for instance.

This has consequences though…

If we only give girls and not boys dolls or beauty sets, it primes them to associate themselves with these interests. Boys can be primed to like more active pursuits by toy tools and cars.

Yet boys clearly enjoy playing with dolls and buggies too, but these are not as typically bought for them. My son cradles a toy baby just as his sister did and likes to push it around in a toy buggy. “Boys in the first years of life are also nurturing and caring. We just teach them really early that that’s a ‘girl skill’, and we punish boys for doing it,” says Brown.

Parents of boys often talk about how they are more boisterous and enjoy rougher play, while girls are more gentle and meek

If from infancy, boys are discouraged from playing with toys we might associate as feminine, then they may not develop a skill set that they might need later in life. If they are discouraged by their peers from playing with dolls, while at the same time they see their mother doing most of the childcare, what does that say about whose role it is to care? And so we enter the realm of “biological essentialism”, where we ascribe an innate basis to a behaviour that is, when you delve a bit deeper, highly likely to be learned.

Toys are one thing, but traits are also prone to gendered stereotyping. Parents of boys often talk about how they are more boisterous and enjoy rougher play, while girls are more gentle and meek.

The evidence suggests otherwise.

In fact, studies show that our own expectations tend to frame how we view others and ourselves. Parents have attributed gender neutral angry faces as boys while happy and sad faces are labelled as girls. Mothers are more likely to emphasise their boys’ physical attributes – even setting more adventurous targets for boys than for girls. They also over-estimate crawling abilities for their sons compared to daughters, despite there being no reported physical difference. So, people’s own biases could be influencing their children, and so reinforcing these stereotypes.

Language plays a powerful role too – girls reportedly speak earlier, a small but identifiable effect but this could be due to the fact that research also shows that mothers speak more to their baby girls than to baby boys. They speak more about emotions to girls too. In other words, we unknowingly socialise girls to believe they are more talkative and emotional, and boys aggressive and physical.

Brown explains that it’s clear why these misconceptions then continue later in life.

We disregard the behaviours that do not conform to the stereotypes we expect. “So you overlook all the times the boys are sitting there quietly reading a book or all the times that girls are running around the house loudly,” she says. “Our brains seem to skip over what we call stereotype inconsistent information.”

Young children are constantly searching for clues about their place in the world (Credit: Javier Hirschfeld/Getty Images)

Parents will also buy their girls toys and clothes typically marketed for boys but rarely the reverse, often in an attempt to be gender neutral.

This in itself gives an interesting insight into how we view gender. Males have always been viewed as the dominant and powerful sex, meaning parents, whether overtly or not, will discourage boys from liking girly things. As Fine explains, “we start to see manifestations of the gender hierarchy – boys seemingly starting to respond to the ‘stigma’ of femininity even in this early period [of childhood].”

It reveals why parents are much more comfortable with girls in boys clothes than boys in girls clothes. Or why growing up as a tomboy attracted positive comments for me – I never liked dolls and loved climbing trees. The opposite occurs for boys who dress or act girly. To be seen as girly or exhibiting feminine traits diminishes status for men – those who do so even earn less.

Gender scholars agree that these preferences are highly socially conditioned – but there remains disagreement about whether any gendered behaviour is innate, for instance, there is evidence that girls who have been exposed to higher levels of androgens in the womb, prefer toys we typically categorise as for boys. Even here Fine points out it could be the environment shaping their preferences. These girls do not consistently show better spatial ability either – a skill that is often said to be better in men.

We also know that babies are extremely sensitive to social cues around them, they can spot differences early on. Regardless of how these preferences develop, it is adults as well as peers who continue to condition and expect certain behaviours, creating a gendered world with worrying consequences.

Women will also do worse on a test if they are first told that their sex typically does worse

For instance, when girls first enter pre-school – a gender gap in maths does not exist, but it later begins to widen as their teacher and self-expectations come into play. This is especially problematic because these reinforced gender stereotypes are “at odds with the contemporary gender egalitarian principle that your sex shouldn’t determine your interests or future”, says Fine.

When specific toys are marketed to boys it could also be changing the brain to strengthen the connections that are involved in, for instance, spatial recognition. Indeed, when one group of girls played the game Tetris for three months, the brain area involved in visual processing was larger than for those who did not play the game. If girls and boys are presented with different types of hobbies, brain changes could naturally follow suit.

As neuroscientist and author Gina Rippon of Aston University explains, the fact that we live in a gendered world itself creates a gendered brain. It creates a culture of boys who feel conditioned to behave in more typically masculine traits – they may get excluded by peers if they do not. If we focus on differences, it also means, as Rippon says, we begin to accept myths such as boys being better at science and girls at caring.

This continues as adults.

Women have been shown to underestimate their abilities when asked how well they scored on maths tasks, whereas men will overestimate their scores. Women will also do worse on a test if they are first told that their sex typically does worse. Of course this could and does affect school, university and career choices.

Even more concerning is the idea that the way some masculine traits are emphasised early on and then conditioned, is linked to male sexual violence against women. We know for instance that the individuals who perpetrate sexual violence tend to be high in “hostile masculinity”, says psychologist Megan Maas of Michigan State University. These are the beliefs that men are naturally violent, need to have sexual fulfilment, and that women are naturally submissive.

Overlooking certain behaviours of girls and boys can contribute to the perception of gender stereotypes (Credit: Javier Hirschfeld/Getty Images)

Studies also show that girls who are heavily into princesses are more concerned with their appearance and more likely to “self-objectify – so they think of themselves as a sexual object,” says Maas. The girls that scored highest on “sexualised gender stereotypes” also downplayed traits associated with intelligence. Early on, both girls and boys have been shown to view attractiveness as “incompatible with intelligence and competence” a study found.

Brown and colleagues have now also argued in a 2020 paper that sexual assault by men against women is so common precisely because of the values we condition onto children. This socialisation comes from a combination of parents, schools, the media and peers. “Sexual objectification for girls starts really early,” says Brown.

One reason that these gendered ideas and self-assumptions continue to exist is, in part, because there are still regular reports of innate brain differences between men and women. However, most brain imaging studies that do not find any gender differences don’t mention gender at all. Or still others are unpublished. This is known as the “file drawer” problem – when no effects are found, they are simply not mentioned or scrutinised.

When we consider situations that might invoke empathy, women and men respond the same, it’s just that from an early age, women have been socialised to act upon this apparently feminine emotion more

And of those that do find small differences, it’s hard to truly show how much culture or stereotyped expectations play a role. Adult brains cannot be neatly categorised into male brains and female brains either. In a study analysing 1,400 brain scans, neuroscientist Daphna Joel and colleagues found “extensive overlap between the distributions of females and males for all grey matter, white matter, and connections assessed“. That is, overall we are more similar to each other than different. One study even showed that women acted just as aggressively as men in a video game when they were told their gender would not be disclosed, but less so when told the experimenter knew if the participants were male or female.

It follows that women tend to be considered as less aggressive and more empathetic.

When we consider physiological responses to situations that might invoke empathy, women and men actually respond the same, it’s just that from an early age, women have been socialised to act upon this apparently feminine emotion more.

This means that in order for there to be any significant change, people have to first understand their biases and be mindful of when their preconceptions don’t fit into the behaviours they see. Even small differences of what they expect of girls versus boys can build up over time.

There is some evidence to suggest mothers speak more to their daughters than their sons, which improves language development (Credit: Javier Hirschfeld/Getty Images)

It’s therefore worth remembering why people are conditioned to think that boys are more boisterous and take note of the times this is not true. My daughter is certainly just as loud – if not more so – as her brother, while he also loves pretending to cook. While these are not necessarily representative examples, they also don’t fit into our ideas of what boys and girls like. It would be easy for me to otherwise have highlighted my son’s propensity to climb on everything and my daughter’s preference for pink, glossing over the numerous times she plays with cars and he with dolls.

When our children do inevitably start pointing out gendered divisions we can help by revising stereotypes with other examples, such as explaining girls can and do play football and that boys can have long hair too. We can also encourage a diverse range of toys regardless of what gender they are intended for. We need to provide as many opportunities as possible “for them to have experiences that go against this sort of avalanche of gendered play”, says Maas.

If we fail to understand that we are more alike from birth than we are different and treat our children accordingly, our world will continue to be gendered. Undoing these assumptions is not easy, but perhaps we can all think twice before we tell a little boy how brave he is and a little girl how kind or perfect she is.

Melissa Hogenboom

AuthorMelissa Hogenboom is the editor of BBC Reel. She is @melissasuzanneh on Twitter.

The gender biases that shape our brains.